As President Donald Trump on Saturday reaches the one-year mark since his inauguration, the U.S. economy is booming. To hear him tell it, this is the happy result of his policies. But while his tax cuts will likely have a beneficial outcome, at least for businesses’ bottom lines, the impact of Trumponomics in other areas is problematic.

Beyond that is the question of the White House’s power to direct a vast and complex $18.6 trillion national economy. Presidents have long taken credit for good economic times, and Mr. Trump is no exception. “American business is hot again!” the president tweeted last weekend.

To Democrats, who say the economy’s rise since the Great Recession occurred mostly on Barack Obama’s watch, this is baloney. David Axelrod, a former Obama adviser and now director of the University of Chicago’s Institute on Politics, countered that Mr. Trump is a “very loud rooster taking credit for the dawn.”

History shows that presidents have a limited impact on the economy’s performance, since broader trends like interest rates and consumer spending aren’t theirs to command. Still, fiscal policy — namely what Washington spends and how — and other executive actions do influence the economy’s course.

“It’s early for Trump’s policies to effect economic change,” said John Lynch, chief investment strategist at LPL Financial. “But there’s good mojo.”

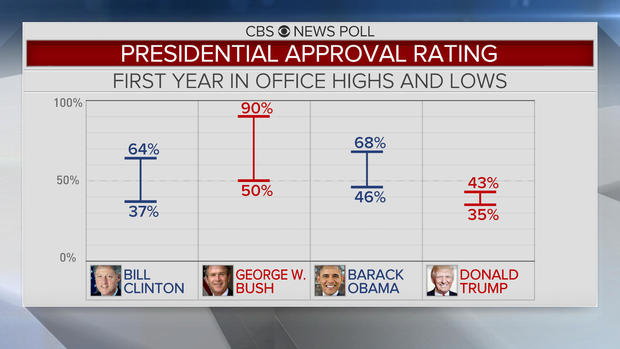

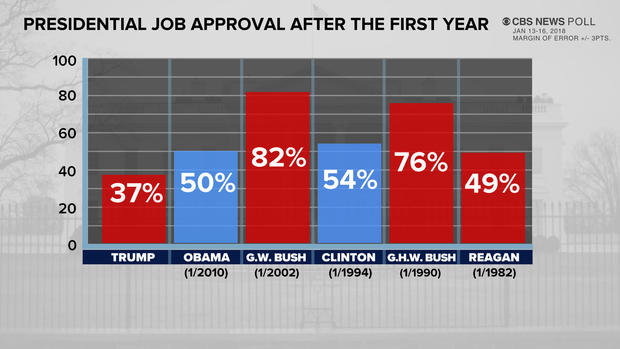

Some 67 percent of Americans say the economy is in fair or very good shape, and 71 percent believe that is partially or mostly because of Mr. Trump’s policies, according to a CBS News Poll released Thursday (see charts at bottom). Even half of the Democrats surveyed give him some credit. At the same time, only 22 percent think they have been directly helped by Trump policies. This comes amid historically low and highly partisan approval ratings, with just 37 percent approving of the job he is doing as president.

Here’s how America’s economy looks after one year of President Trump:

Economic growth

The respectable increase in GDP during the Trump administration’s initial year seems to support the narrative that the economy is once more on the march. The first quarter of 2017, when Mr. Trump took office, posted subpar 1.2 percent annualized gain. But the second and third quarters, with the Trump team fully in charge, showed substantial acceleration, with growth of 3.1 percent and 3.2 percent, respectively. And many GDP forecasts for 2018 project similar or even faster growth.

Regardless of who deserves credit, this is welcome news. Since the recession, which ended in Mr. Obama’s first year as president, GDP growth averaged around 2 percent annually, an anemic pace historically. Rebounds from major downturns tend to be more robust.

There are many explanations for this, such as shell shock from the financial crisis keeping business and consumers wary. In fairness, the Obama expansion record also had its buoyant moments. Example: After GDP of minus 1 percent in the first quarter of 2014, growth leaped to around 5 percent in the second and third. But then it slowed to just a 2 percent advance in the fourth.

Today, the so-called animal spirits — legendary economist John Maynard Keynes’ term for widespread optimism that leads to investing and other upbeat economic activity — are back. Consumer confidence is high, consumer spending is solid, capital expenditures (companies’ outlays for plants, equipment and kindred steps to enlarge their operations) are once more climbing, and after years in the doldrums, wages show signs of picking up. Pay rose at an annual rate of 2.5 percent in December, and research firm Oxford Economics believes this could go up a full percentage point higher by year-end.

While these glad tidings can be chalked up to an expected, if belated, recovery from the recession, the Trump tax cuts appear to be a factor in boosting confidence, particularly among businesses. The tax bill, which Mr. Trump signed right before Christmas, slashed the corporate tax rate to 21 percent from 35 percent, making the U.S. more competitive with other major economies, and allowed the immediate write-off of capital spending, instead of spreading it over several years — all boons to corporate profits.

The tax plan aims to pump $1.5 trillion worth of breaks into the nation’s economy over the next 10 years. Although the bulk of the benefits go to companies and the wealthy, ordinary folks will get something, too. The average tax reduction for the middle fifth of American taxpayers by income will be $800 in 2019 and $55,000 for the richest 1 percent, estimates from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy contend.

“The extra income is bound to help them in the short run,” said David Swenson, an Iowa State economist. By Oxford Economics’ projections, this stimulus should add 0.4 percentage points to GDP growth in 2018.

Jobs

During President Obama’s first year, 2009, the recession-racked unemployment rate continued to climb until it peaked at 10 percent in October. By the time he handed the Oval Office over to Mr. Trump last January, joblessness had fallen to 4.8 percent, and during the first Trump year it dropped to 4.1 percent. In 2017, the economy added 2 million jobs. Some economists think the unemployment rate will dip further this year, to as low as 3.5 percent.

So right now, the country is in a blessed situation called “full employment,” in which workers are in demand — perhaps one reason wages at last have begun to nudge up.

As a candidate and as president, Mr. Trump has pledged to restore the nation’s manufacturing base, which technology and cheap overseas labor competition have eroded. At the end of World War II, a quarter of American jobs were in factories. Today, it’s around 9 percent.

Numerically, manufacturing jobs topped out at 19.4 million in 1979 and dipped to a recession low of 11.5 million in 2009. It has been crawling back ever since. In December, manufacturing employment rose by 25,000, mostly due to a gain in durable goods industries. The factory sector generated 196,000 new jobs in 2017.

Whether Mr. Trump is the catalyst for this latest increase or merely its heralding rooster, he has made a point of badgering U.S. companies to stop exporting jobs to lower-cost locales like Mexico. Just prior to taking over, the soon-to-be president pressured air-conditioner maker Carrier, a unit of United Technologies (UTX), to keep 1,000 jobs in Indianapolis rather than ship them south of the border. Carrier, however, has still cut several hundred jobs there.

Delivering on his job promises will be difficult in other instances as well. Consider coal mining, which Mr. Trump has targeted for a rebound. Despite relaxing regulations on environmental standards, employment in this industry remained stagnant in 2017, at just over 50,000, as utilities continue their ongoing shift to cleaner and cheaper natural gas. That employment figure is down from almost 90,000 in 2011.

Meantime, Mr. Trump and GOP lawmakers are mulling cutting the number of legal immigrants, now 1 million yearly, in half. The president believes these immigrants bring crime and terrorism to U.S. shores and swipe American jobs. However, such a draconian approach would harm growth, Simon Johnson, former International Monetary Fund chief economist, argued at a recent public forum. And it means economic goals “are going to disappear like sand through your fingers,” he said.

Trade

Mr. Trump’s strident “America First’ rhetoric is far from empty. Among one of his first gambits was to pull the U.S. out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a 12-nation trade pact designed to create a common market. The president complained that it would cost American jobs.

The next trade treaty in his gun sights now is the North American Free Trade Agreement, a deal among the U.S., Canada and Mexico signed in 1993 by President Bill Clinton, which mostly eliminates tariffs. Mr. Trump, however, charges that it eases the transfer of U.S. jobs to lower-wage Mexico. Axing NAFTA could lead to higher prices in the U.S. and harm U.S. exporters, especially farmers, critics say. As Iowa State’s Swenson put it: “Mexican legislators are saying: ‘Why get corn from Iowa when we can go to Argentina?'”

The risk is that Mr. Trump could start a full-scale trade war, with devastating consequences. In the presidential campaign, he vilified China as a currency manipulator and job thief, yet initially as president he made nice with Beijing in hopes of getting its help in ending North Korea’s nuclear buildup.

That didn’t go anywhere, so now Mr. Trump is taking the hard line again. He has griped to Chinese leader Xi Jinping that the U.S. trade deficit with China is “not sustainable.” The administration may soon announce tariffs or quotas on Chinese washing machines and solar panels. In the wings are even harsher tactics, like banning Chinese investments in the U.S.

Such talk has many fearful of a reprise of the trade disputes that deepened the Great Depression. A less-dire scenario has the rest of the world striking deals and liberalizing trade, while the U.S. languishes on the sidelines. “The U.S. economy will suffer as others move forward and we stay in the same place,” warned Simon Lester, a trade analyst with the Cato Institute.

Stock market

Slightly more than half of Americans invest in the stock market, whether through owning individual shares, mutual funds or retirement accounts like 401(k)s. So its fortunes have a bearing on the “wealth effect,” the belief among consumers that they are well off, thus encouraging them to spend and invest further, goosing economic growth.

Since the 2016 election, domestic stocks and Wall Street’s long-running bull market have gotten a new tailwind, with talk of tax cuts, along with deregulation and massive infrastructure spending. The last item has yet to happen.

In his eight years, Mr. Obama saw the S&P 500 rise 181 percent, albeit off a low base owing to the recession. During his first year — the market bottomed out in March 2009, almost two months after his swearing-in — the S&P climbed 46 percent.

By contrast, in Mr. Trump’s maiden year, the benchmark stock index was up less, 23 percent, which admittedly was building on a long ascent from the Obama era. The market’s “Trump Bump” came after moving sideways for 2015 and much of 2016, amid plunging oil prices, which damaged other commodities too, and fears that China’s growth was slowing.

For this year, continued strong earnings growth is expected. FactSet researchers place it at 14.7 percent, but they project that the S&P 500 will rise 6 percent, less than a third of the 2017 showing. That likely reflects a fatigue after such a heady ascent.

Like Ronald Reagan, Mr. Clinton and Mr. Obama, President Trump must hope that he can cruise through his term without an economic problem. All three of those previous presidents endured recessions at the outset of their tenure, downturns that began under predecessors. And they finished their presidencies amid pleasant economic conditions.

Mr. Trump has striven to own the economy as a point of pride. So if it falters — and the odds are it will at some stage — he risks looking doubly bad.

CBS News

CBS News

© 2018 CBS Interactive Inc.. All Rights Reserved.